With salary arbitration hearings beginning on February 1st

let’s take a look at the winners and losers of this process.

Before we look at winners and losers it is first

important to understand the process.

A player becomes arbitration eligible twice under his entry-level

contract: Once in his 3rd

or 4th year, depending on when he is called up during a season, and

then two years after that. So a

team essentially holds the rights to a player for six years after he is

drafted. If a player becomes

arbitration eligible and does not come to an agreement with his club, then both

the club and player submit a salary number that they feel is fair and a panel

will hear the case. The panel then

decides which salary number best reflects the player’s worth and that is the

amount he will earn in the upcoming season. A player can also be offered arbitration if he is a free

agent and the club and player do not come to an agreement before the

arbitration period.

Salary arbitration in Major League Baseball started in 1974

with the purpose of adjusting player’s salaries to better represent their play

on the field while still under an entry-level contract. This offseason, 142 players filesd for

arbitration. Most of these players

reach agreements with their teams before the process reaches the point of

having a hearing, but since 1974 there have been 495 cases heard by arbitration

panels. The process has clearly

become a big part of the MLB offseason so who are the real beneficiaries of it:

the players or the owners?

When looking at the process from a numbers standpoint alone

the players obviously benefit. In

2010, the 128 players that filed for arbitration had an average salary increase

of 107 percent, meaning that on average players were making over double what they

were in the previous season. However

this number is very skewed by players who have seemingly reached the primes of

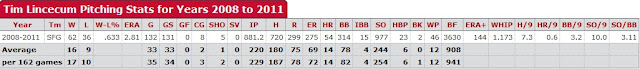

their careers early. Take the

Giant’s Tim Lincecum for instance who received the biggest raise during the

arbitration period of any player in 2010.

Lincecum’s salary increased from $650,000 to a two-year, $23 million

dollar contract. Lincecum was

seeking $13 million in arbitration while the Giants offered $8 million, but

like most cases there was an agreement before a hearing. This increase in salary was 1,131

percent. This is a huge number

that may come off as unfair to the owners because of his age at the time, but

Lincecum’s case is unique because of his two Cy Young awards. Because Lincecum only signed a two-year

deal, he is again arbitration eligible in 2012. He is asking $21.5 million which is just short of Roger

Clemens record request of $22 million in 2005, while the Giants have offered

$17 million. The $17 million the Giants

offered broke the previous record of the $14.25 million the Yankees offered

Derek Jeter in 2001. The

arbitration benefits players who have enjoyed early success greatly because

they could still be making a salary around the league minimum ($480,000) and

consequently hurts the owners for the same reason.

When looking at the process from a numbers standpoint alone

the players obviously benefit. In

2010, the 128 players that filed for arbitration had an average salary increase

of 107 percent, meaning that on average players were making over double what they

were in the previous season. However

this number is very skewed by players who have seemingly reached the primes of

their careers early. Take the

Giant’s Tim Lincecum for instance who received the biggest raise during the

arbitration period of any player in 2010.

Lincecum’s salary increased from $650,000 to a two-year, $23 million

dollar contract. Lincecum was

seeking $13 million in arbitration while the Giants offered $8 million, but

like most cases there was an agreement before a hearing. This increase in salary was 1,131

percent. This is a huge number

that may come off as unfair to the owners because of his age at the time, but

Lincecum’s case is unique because of his two Cy Young awards. Because Lincecum only signed a two-year

deal, he is again arbitration eligible in 2012. He is asking $21.5 million which is just short of Roger

Clemens record request of $22 million in 2005, while the Giants have offered

$17 million. The $17 million the Giants

offered broke the previous record of the $14.25 million the Yankees offered

Derek Jeter in 2001. The

arbitration benefits players who have enjoyed early success greatly because

they could still be making a salary around the league minimum ($480,000) and

consequently hurts the owners for the same reason.

As steep a price the owners may have to pay, they

are still the main beneficiaries of the process. There is no better system for owners in professional sports

than the MLB’s arbitration process.

In the NFL first round picks have previously been guaranteed north of

$50 million dollars and fizzled out before doing anything productive in the

league. The MLB arbitration

process allows for six years of evaluation of a player before a team has to

commit to him long term. And if

during those six years there has not been major progress in a player’s

development, his annual salary will hover right around the league minimum. Every once in a while there is a player

who develops into a stud long before he is supposed to, which makes owners

cringe at the process. But in reality they are the party with all the leverage.